Introduction

In the last part I talked about various ways of representing word as vectors in NLP. However, most state-of-the-art models (as of 2020 anyway) do not even care about word vectors at all! So what happened?

It should be obvious that using word vectors leave out an important aspect of all languages: word context. Words should not be treated individually, because a single word can have multiple and vastly different meanings in different contexts - consider content in table of contents and I am content with my job.

In the end, most applications of NLP would require using sentences or even paragraphs or documents level representations. Examining word vectors remain mostly useful for analyzing and validating linguistic properties. That's why this part will probably drag out way longer than the first.

Progress on sentence representation

1. Bag of Words

The original bag of words model involve counting occurences of words and putting inside a fixed-size dictionary vector. This is one-hot encoding on the sentence level - as illustrated below:

A dictionary such as:

["the", "quick", "brown", "fox", "jumps", "dog", "like"]Would represent the sentence I like dog but I do not like fox (forgive the grammar, it's beside the point) as:

| the | quick | brown | fox | jumps | dog | like |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Which is actually the sum of one-hot encoded word vectors!

Using word vectors, the bag of words model is either the sum or the average of word vectors - not necessarily one-hot encoded vectors, but often the pre-trained Word2Vec, GloVe or FastText vectors I mentioned in part 1.

As immediately evident, this method disregards contextual information and word ordering. Used for sentence/document classification, it would be a glorified checking substrings algorithm.

SIF and FastText

One attempt to improve upon this method is to use a weighted average instead. This can be considered a direct improvement over removing stop words - we can use TF-IDF weighting scheme to determine the weights of word vectors, or a improved version - smooth inverse frequency (SIF). This method is implemented in A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings - which actually outperforms several more complex models that actually takes into account word ordering (*on select tasks) - some of which we will explore later on in this article.

- Implementation: PrincetonML / SIF (Github)

If you tried to google for FastText, you might also have seen the paper Bag of Tricks for Efficient Text Classification . This paper actually employs a similar method to vanilla bag of words - to take a (normal) average of word vectors. The difference here is it also encodes n-grams of words as separate tokens, which gives it a form of word order information.

For example, the following sentence:

The quick brown fox jumps

Can be broken into these tokens (assuming a 2-gram model):

<the>, <quick>, <brown>, <fox>, <jumps>, <the quick>, <quick brown>, <brown fox>, <fox jumps>

Then encoded and averaged into a sentence vector.

- Tutorial: Text classification using FastText

- An approximate implementation that can give a good understanding on how FastText works lie in the Keras examples.

- Pytorch also has an implementation of this method in its examples documentation

A honorable mention: this method bears homeage to Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification, where the use of convolutional network bears resemblance to this method of taking n-grams into account. Though empirically, this method of using CNNs might not necessarily outperform the various Bag-of-Words variations above, and is more computationally expensive.

References:

- A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings

- Bag of Tricks for Efficient Text Classification

- Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification

2. Skip-Thought Vectors

Note that by this time - People are not longer strangers to using recurrent networks (GRU/LSTM) for machine translation. This is, to my knowledge, the first attempt on applying Machine Translation to self-supervised training. The paper also introduces BookCorpus, which is a dataset that is often used to this day in combination with Wikipedia for training language models.

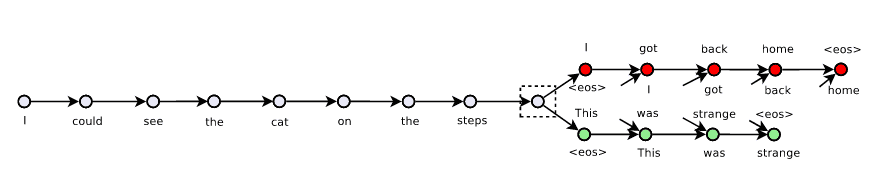

The training objective of Skip-Thought Vectors is to generate (or "translate") the previous and following sentence for any given sentence (similar to Word2Vec's skip-gram setup), as illustrated below:

Skip-Thought Vectors training objective

Side note: This paper also introduces an interesting technique for handling unseen words: It trains a linear mapping between Word2Vec and its encoder's embeddings layer for shared words. After that, unseen words can be taken from Word2Vec and mapped to the model's embedding space. This does seem to work decently from the examples given by the paper.

All in all, the 2 most important contributions of this work is the BookCorpus dataset and it paved the way for sentence embeddings by proving that it can outperform existing techniques. It demonstrated the viability of training a sentence-level encoder that's able to perform transfer learning and benefits downstream tasks (with obvious parallels to ImageNet). However, Skip-Thought was a huge model for its time (Bi-directional LSTM, 4096 dims and trained for a month), and it was quickly demonstrated that the training objective used in the paper was actually excessive, as the trend for the researches that follow gear towards computational efficiency.

Quick-Thought Vectors

With Skip-Thought vectors being the giant model that it is (even with now - in 2020 terms of hardware), the focus then shifted to finding ways to achieve the same sentence-vector results. Quick-Thought Vectors first demonstrated that a 3-way classifier can perform just as well - or even better, while being able to train much, much faster.

Important side note:

The reason for this faster training speed will be very relevant later on, so it's important to keep in mind: one of the biggest bottlenecks for NLP networks is very often the Softmax layer. The softmax operation is heavily used for classification. In the case of machine translation, the model actually classifies the next word - so there are as many classes as there are words in the vocabulary - which usually goes up to 20.000, 30.000 to 50.000 words at the time.

For translation, this also repeats for as many times as the decoded sentence's length. Hence why, with Quick-Thought being able to reduce this to only 3 classes, massively sped up the training process.

InferSent

This paper by Facebook AI Research (massive props to them) is actually not a great achievement in the grand scheme of things, but I find the paper interesting to read because the idea is simple and because of how extensively the authors evaluated alternatives (and spoiler: finding the simple bi-directional LSTM outperforming more complex methods). They also forgoes the Embedding layers in favor of vanilla word vectors, which massively reduces the size of the model and time to train: The model can be trained on a single consumer-grade GPU within a day.

The model is conceptually extremely simple: Word vectors > 2-layer Bi-directional LSTM > feed-forward and 3-way classifier, trained on NLI/SNLI datasets (which labels pairs of sentences on whether it entails each other, contradicts, or neutral). The problem with this model is that it's supervised. A good labelled dataset such as NLI/SNLI is obviously hard to obtain for other languages than English.

Side note: I absolutely recommend digging up the repository's commit history to find the original implementation with the alternative encoders and training code like here.

References:

- Skip-Thought Vectors

- An Efficient Framework for Learning Sentence Representations

- Supervised Learning of Universal Sentence Representations from Natural Language Inference Data

3. Language Models

Language Models are a class of models which objective is to predict the next word (or character) in a sentence - think of the auto keyboard suggestions on modern smartphones. These models can be trained efficiently because each training batch is usually dense. They can also be trained in an unsupervised manner: as long as there is text you can train a language model on it.

Summary of the training task: Source: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy Target: quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

These are some of the easiest class of models to implement, so they are also good for benchmarks on sequence networks. As such, later on I will also mention when it is used for Transformer-type networks.

As can be seen, because of the training task, language models are uni-directional, which means at every timestep, the meaning of the word is only considered by taking into account words before it and not after. There is one workaround by concatenating results from a left-to-right and right-to-left models, but they are not strictly bidirectional. Emperically, there is always performance to be gained from changing a unidirectional model to a bidirectional model.

Despite that, over the years, it was proven that unidirectional language models can be both easy to train and enough adequate to be used for transfer learning. For the LSTM era, this was most prominently demonstrated and pushed forward thanks to the following papers:

Regularizing and Optimizing LSTM Language Models (AWD-LSTM - Salesforce)

This paper demonstrated that a heavily regularized and hyperparameter-searched language model can greatly outperform naive counterparts. It also demonstrates a language model trained within a day on consumer-grade GPU. However, despite its touting a new recurrent network variant QRNN as a drop-in replacement for LSTM, QRNN quickly became unpopular due to its expressiveness being inferior to LSTM. However, it became an important starter codebase and baselines for a plethora of models that come out after.

Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification (ULMFIT - Fast.ai)

This paper quickly became a standard as it demonstrated ways to train a language model efficiently and how to, afterwards, apply to downstream classification tasks with impressive results, with just small modifications to existing code. It popularized tricks such as linear warmup-decay learning rate schedule and "gradual unfreezing" when training on downstream classification. Unfortunately it never became too popular because ELMo (which I detailed in part 1 of the series) was released very soon after and became the new standard thanks to its superior performance. However, to this day, ULMFIT can still be considered as a quick and dirty baseline to any classification tasks.

References:

- Regularizing and Optimizing LSTM Language Models

- Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification

4. Other improvements

Around this time, various other non-architectural tricks have also been employed and incorporated into models. These are just as important in terms of efficiency, and some are still widely used.

Sub-word and Byte-pair encoding tokenization

Sub-word segmentation and BPE has become a standard to solve the out-of-vocabulary issue. For a bit of background: in the word vector era, pre-trained word vectors would have in the 800k - 6 billion words. It was simply not viable in terms of computational and memory resources to use that many classes for neural network models. Therefore all models with embedding layers usually reduce this vocabulary size to around 50k or even 20k most common words. This often leaves words that don't exist in the vocabulary and would often have to be replaced with a representative _unknown_ token.

Sub-word segmentation is a mid-ground workaround for the issue: For example, by segmenting "performer" into "perform##" and "##er", and "player" into "play##" and "##er", we can reuse the token "##er" that the 2 words share, and also use the token "perform##" for "perform##"+"##ance". This also potentially helps embed prefix and subfix grammatical meanings (e.g "-er" usually represents people) into the model.

The solution is not perfect - however - there can still be out-of-vocabulary tokens and there are cases where the segmentation algorithm cannot work perfectly.

Side note: Character-level models would obviously be the way to perfect representations that will have no out-of-vocabulary issue - hence it was actually employed partly in ELMo. However, this would significantly increase the tokens count in each sentence, which is both computationally expensive and causes forgetting in LSTM networks, which generally leads to inferior performance compared to word-level or subword-level models.

Weight-tying for embeddings

Normally, language models are extremely similar to neural machine translation models - save for one part: the input and output vocabulary are the same for language models. Since the output layer is usually a linear (vocabulary size x hidden size) layer, which is often the shape of the embedding layer, their weights can be tied to save a lot on memory consumption and provides a small regularization effect. This trick was employed in AWD-LSTM.

Adaptive softmax

By dividing softmax classes into smaller clusters, exploiting natural word distribution, this trick helps massively speed up softmax computation on GPUs for vocabulary size of around 50k and over. This can massively help training neural machine translation models and language models on consumer-grade GPUs. It has reduced efficiency for smaller vocabulary sizes, however, hence it is not often employed in recent models where the vocabulary size often settles at around 30k.

References:

- Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units

- BPE-Dropout: Simple and Effective Subword Regularization

- Using the Output Embedding to Improve Language Models

- Efficient softmax approximation for GPUs

In the next part of the series, I will discuss on Transformer models - which have been the state-of-the-art for the past few years and being all the hype in NLP to this day, which I feel should warrant it a dedicated article. Stay tuned!